Thinking Like a Network Scientist Makes You a Better Networker

This article is adapted from a presentation by our CEO, Dr. Danielle Varda, called Thinking Like a Network Scientist. Click here to watch the session.

Two decades ago, public and nonprofit sector leaders started to cultivate a new practice called ‘the network way of working.’ In an effort to break down silos and avoid duplicating their efforts, community organizations started building networks of like-minded partners. After twenty years of practice, this approach has become a standard norm in the field, with leaders expected to build and manage networks to reach shared goals. However, the evidence base to inform these network approaches hasn’t kept up. People are spending more time and resources than ever before to build bigger networks but lack the necessary tools to evaluate the impact of all these new partnerships.

Network Science: An evidence-based tool for better network strategies

Network science has the potential to address this problem by providing us with powerful evidence-based insight specific to networks. By collecting relational data and creating network maps, network scientists draw conclusions about the relationship between the way a network is structured and the outcomes that it produces. These methods and theories are a powerful set of tools for those using a network approach. In this article, we will share some lessons and ideas originally proposed by our CEO, Dr. Danielle Varda, in her popular training session, “Thinking Like a Network Scientist.”

What do we mean by networks and network science?

When we talk about networks, we’re talking about an interconnected group of people and organizations. Some networks are formal, like coalitions and associations, while others are informal gatherings without any official or known list of participants. They form for many reasons: advancing research, sharing information, disseminating new tools or creating space to learn collectively. However, most networks share some crucial traits: They usually operate without hierarchies, relying on trust and influence rather than power or authority like a traditional organization.

Network scientists use several methods to study networks, including social network analysis. They start by collecting relational data, which consists of structural factors like who works with who, and quality factors, like how much each partner trusts those they work with. This data can be visualized as network maps, which represent the connections within the network using a series of nodes and lines. Quality data metrics, like trust or value, are visualized by changing the color, shape, or size of nodes and lines to create more insight.

Ultimately, by comparing network attributes with their eventual outcomes, network scientists test theories about how certain structures or qualities impact the success of the network over time. This is how many of the most important network science lessons were discovered.

The Advantages of Strong and Weak Ties

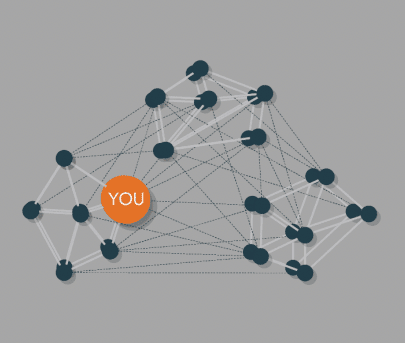

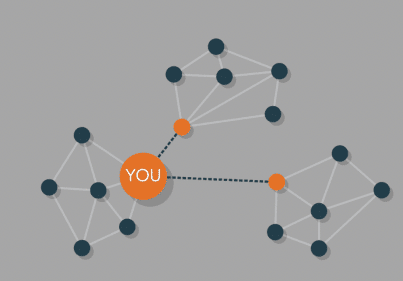

One of the most fundamental network principles is that more is not (always) better. Consider for a moment your own social network, like the orange node in the network to the left. We often form ties and relationships to those who are similar to us. They may share similar beliefs and values, go to the same places as we do, and access many of the same resources. This principle is known as homophily – a tendency to connect to those similar to us (Ex. birds of a feather flock together). These ties with those similar to us, who are often our friends and family, are called “strong ties.”

However, as we get out into the world, we increasingly connect to people outside our immediate associates. These acquaintances often think differently than we do, access different resources, and navigate different social groups. Because we have less in common and often interact less, we call these ‘weak ties’. A study by Mark Granovetter in 1973 analyzed how people find jobs through their networks. Contrary to expectations, he found that most people learn about job opportunities through weak ties – their acquaintances rather than their friends. However it makes sense upon closer inspection, as weak ties have access to new sources of information, while our strong ties probably know about most of the same jobs as we do. We call this tendency to learn more novel insight from our weak ties is known as ‘the strength of weak ties’.

More is Not (Always) Better in a Network

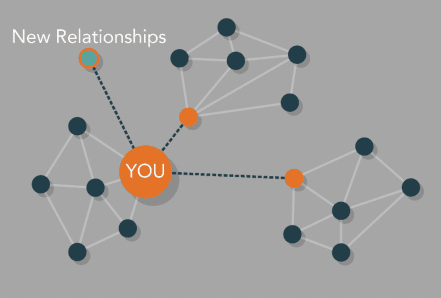

Unfortunately, as more organizations learn about the strength of weak ties, they often draw a simplistic conclusion: If we want to learn about more novel opportunities, innovations, and resources, we should try to build as many weak ties to new partners as we possibly can. Right?

Well, not always. Networking takes time, energy, and resources. Each new relationship costs you something to develop and maintain. We call this your ‘relationship budget’- the limit to your collaborative capacity for creating and managing new partnerships. Among those taking a ‘more is better’ approach, no one was thinking about their relationship budget and how to spend it most wisely. It wasn’t efficient or effective, and people were burning out. There had to be a better way.

Structural Holes: A Better Way to Network

Ron Burke studied this issue from an individual network perspective, and looked at the issue of redundancy in networks. When we try to network with everyone in the community, the result is a large number of redundant ties, where multiple people are connected in multiple ways. Burke pointed out that these redundancies quickly drain resources and time, while providing little additional benefits. If we can find ways to connect to members of our network through other pre-existing intermediaries in the network, it frees up time and resources to build new partnerships with those we were not previously connected to. This creates tangible new benefits, like access to new opportunities, information and ideas, without creating redundancy. Burke calls these intentional gaps between partners ‘structural holes”, another key network science theory.

We Need the Right Data to Manage Networks Strategically

So how do you start analyzing your network to build more weak ties, integrate structural holes, and manage your relationship budget strategically? The key is taking a data-driven approach to analyze your network.

Nearly a decade ago, Dr. Varda recognized the need for new tools that make network science insights available to those funding, building, and leading cross-sector networks. So she decided to build one herself to fill the gap. The result was PARTNER, our community partner relationship management platform. It includes tools to survey your members, gather relational data, and visualize your connections — helping to create network maps with ease, identify key insights and share them in custom reports. As a result, network science is a tool available to any network to begin mapping their network, identifying insights, and building a strategy to improve, together.

Click here to learn more about PARTNER CPRM.

Related Read: The Benefits of Community Partner Relationship Management Software

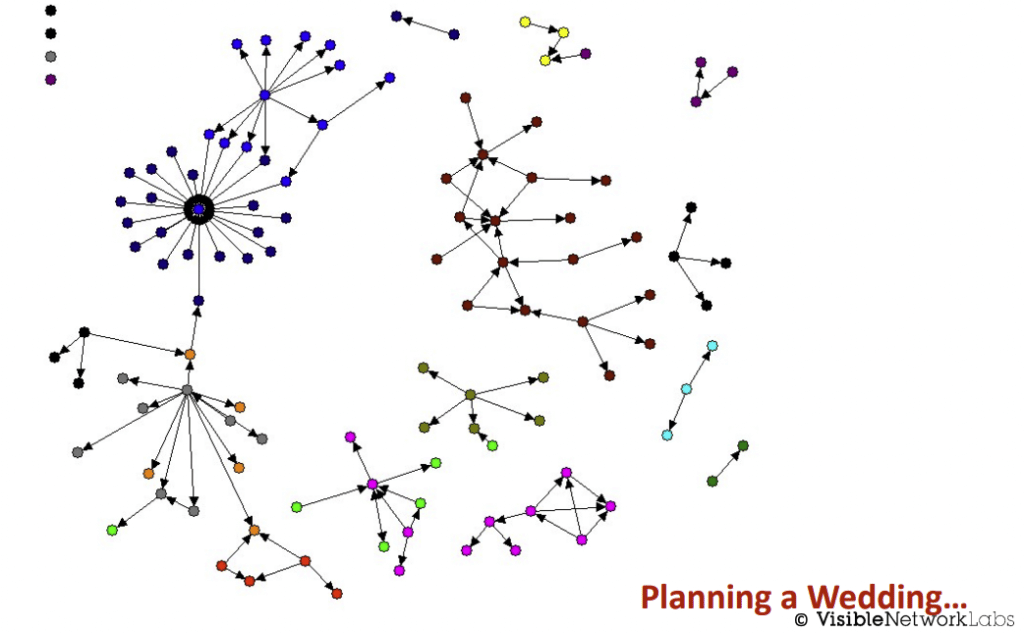

An Example of Network Science Applied in Daily Life

When Dr. Varda first got engaged, she debated over the right way to seat guests. She told me, “There are two basic approaches. Either you seat people according to whom they know, or you intermingle people so that they all meet new people. But we didn’t know which was best.” As a network scientist, she decided to take a data-driven approach and sent all of her guests a short network survey. She quickly noticed some major differences between her husband’s network and her own. As a midwesterner, his network was very closely knit. Everyone tended to know other members of the network. Dr. Varda’s network on the other hand was full of holes – with some sub-networks completely isolated from the other groups. They ultimately decided to seat people by those they knew, since they could see how interconnected the group was, a good example of how network science and social network analysis can inform the way we build networks.

Networks are Powerful But Only With Data and a Strategy

Clearly, networks have enormous potential to change the way we approach our work. However, it is important to keep a strategy in mind rather than adopting a ‘more is better’ strategy. Thinking like a network scientist and using tools like social network analysis can provide the data and insight necessary to go from guesswork and intuition to an evidence-based approach. PARTNER CPRM remains the best tool to make the change and adopt your own data-driven network strategy. Click here to learn more about PARTNER CPRM or click here to request a free web demo.