A Call for Social Resiliency 10 Years After Hurricane Sandy

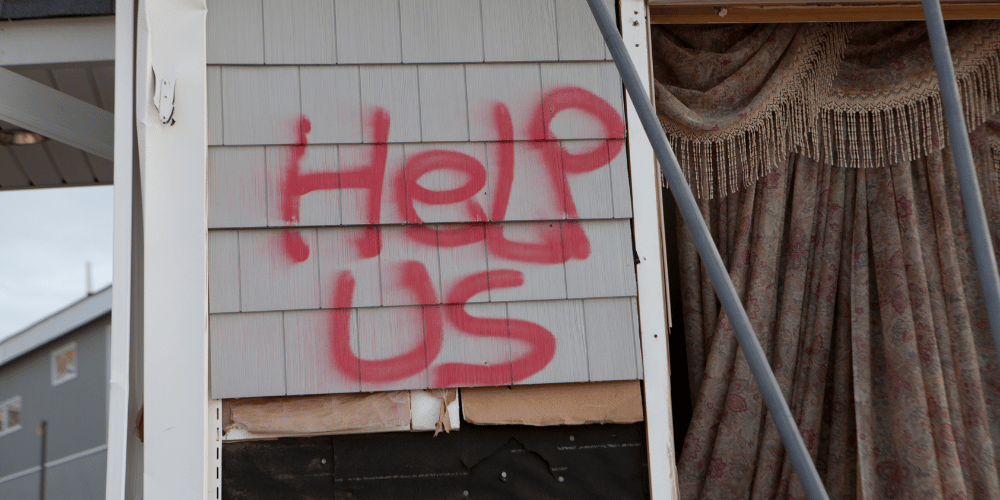

It is hard to believe that ten years have passed since Hurricane Sandy destroyed much of the eastern coastline. It has taken years to recover from the superstorm’s record-breaking storm surge, with many areas still working toward recovery. Neighborhoods across New York City and the broader Mid-Atlantic region faced an unprecedented emergency, exposing the strengths and barriers facing the most marginalized communities.

In the aftermath of the Hurricane, I had the privilege of engaging local community organizations as a research assistant with the Superstorm Sandy Research Initiative at the Institute for Public Knowledge at New York University. While working on the ground with community organizations to better assess and understand the impact of Hurricane Sandy across communities in New York City, I had the opportunity to learn firsthand about the social vulnerability factors that influence the effects of natural disasters.

Leveraging Community Networks to Respond to Disasters

It became clear that active community networks across NYC communities stepped up to play critical stabilizing and supportive roles in affected areas in the aftermath of the storm. Numerous institutions that serve as pillars of the existing social network worked together to organize neighborhood response activities during and after Sandy. Residents affected by the tragedy turned to these organizations, which they had not anticipated would be involved in disaster response since they had a strong sense of trust in their track record of meeting local community needs.

These neighborhood organizations and networks were able to locate and organize aid, distribute supplies to areas with a high need, and help marginalized groups of people, including the elderly, individuals with disabilities, non-English or limited English-speaking community members, and those living in remote areas. Communities that overcame the devastating effects of the Hurricane sooner were those with very tight-knit community groups, coalitions, and engagement. Communities with more robust and involved social networks were better equipped to use these networks to prepare for, respond to, and recover from Hurricane Sandy (Klinenberg, 2018).

Social Capital Improves Community Resilience in Disasters

These social networks are valuable because of social capital, which is a community’s built-up sense of trust, value, and dependability. This is increased through recurring behaviors and pursuits that promote interpersonal interaction, such as attending neighborhood gatherings, engaging in community activism, or playing in a local sports league. Social capital influences a community’s resilience in the face of crises and disasters.

This concept has been the topic of study for Eric Klinenberg, Professor of Sociology and Director of the Institute for Public Knowledge at New York University. His seminal work concentrated on the 1995 Chicago heat wave, which claimed 739 lives—roughly seven times as many as Hurricane Sandy did. According to his research, there was a significantly lower fatality rate during the lethal heat wave in Chicago communities with vibrant streetscapes, thriving civic activity, and robust community groups that naturally bring people together (2002).

Community Connectivity Increases Community Resilience

A community’s capacity to remain resilient in the face of social, economic, and environmental shocks is significantly influenced by its social networks. Looking at community resilience more broadly, those pre-existing communication and interaction patterns enable better information transmission, coordination, and resource allocation during an emergency, as we observed in many communities after Superstorm Sandy.

In contrast to trying to identify the correct person you may not know during an emergency, relationships developed long before any crisis arose are significantly more helpful and efficient. Because government and disaster response organizations have a limited capacity to respond during such a large-scale emergency, many neighborhoods with less urgent needs or limited access to these services and organizations must rely on their communities in the immediate aftermath. This has become an increasingly important concept for civic leaders, policymakers, and funders in the wake of Superstorm Sandy.

Lessons Learned from the Hurricane Sandy Response

There are numerous important lessons to be learned from how neighborhood community groups in New York City were able to use their social capital to respond to Superstorm Sandy, including two significant areas of social networks: activated civic engagement and community hubs.

Activated Civic Engagement Makes a Big Difference

Many impacted groups were able to respond quickly to Superstorm Sandy because of local personnel who were integrated into neighborhood life. Some staff members were already in the area when the transportation and communication systems failed, conveying needs and acting to assist the locals. Active civil society organizations like the Rockaway Youth Task Force, who were prepared and ingrained in the neighborhood, were able to engage residents as some of the best crisis responders after Sandy. In terms of long-term resilience, the group began urban gardening to increase neighborhood access to healthy food after Hurricane Sandy wrecked establishments that were not restored, including supermarkets.

The Importance of Community Hubs & Gathering Spots

Local gathering venues are essential to neighborhood residents’ relief and recovery activities. Locals in need flocked to community organizations that had been a dependable source of services for the community for years in the wake of Superstorm Sandy. Neighborhood-based groups are uniquely situated in the neighborhood to coordinate and disperse relief since they are easily known and accessible. Groups such as the Rockaway Beach Surf Club were able to step in as a well-known venue and work with neighborhood residents as a central community and communication hub, providing supplies and additional resources for the Rockaway community (Klinenberg, 2018).

Data Continues to Demonstrate the Importance of Connectivity

Two years after Sandy, researchers at the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research (AP-NORC) found that neighborhoods deficient in social cohesion and trust struggled more to recover after Sandy (2014). According to the data, residents of communities taking longer to recover are less likely to think that people can be trusted or that the storm brought out the best in them. They are also more likely to report more food and water hoarding, looting and stealing, and vandalism in their communities. As their research alludes, a network’s capability or resiliency in an emergency might be determined by the level of social cohesion present.

To best address continued recovery and long-term resiliency across community networks, organizations must begin to better understand and assess social connectedness across their networks, particularly across the most marginalized communities they engage.

Resources to Improve Disaster Resilience, Response & Recovery by Strengthening Community Connectivity

Visible Network Labs and RAND Corporation utilized these lessons, specifically for health departments alongside community-based organizations, by creating the “Partnerships for Recovery Across the Sectors (PRACTIS) Toolkit.” The purpose of the PRACTIS toolkit is to help local health departments identify the key community-based organizations that contribute to disaster response and recovery, offer guidance about the strengths and weaknesses of partnerships between local health departments and vital community-based organizations, and provide an engaging exercise that can improve the relationship between local health departments and crucial community-based organizations (Acosta et al., 2015). Combined, these three tools create a comprehensive process for improving recovery partnerships.

To continue improving partnerships, it is recommended that these tools are used repeatedly to help continually improve partnerships across local community organizations and governments. Additional considerations to emphasize the importance of activated civic engagement and community hubs utilizing these tools should be made to work toward social resilience across networks.

For More Information:

Acosta JD, Chandra A, Xenakis L, Varda DM, Eros-Sarnyai M, Eisenman D, Gonzalez I, Gutierrez J, Glik DC, and Sprong S. (2015). Partnerships for Recovery Across The Sectors (PRACTIS) Toolkit, RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/tools/TL188.html

AP-NORC. (2014). Two years after superstorm Sandy: Resilience in twelve neighborhoods. https://apnorc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Sandy-Phase-2-Report_Final.pdf

Klinenberg E. (2002). Heat wave : a social autopsy of disaster in chicago. University of Chicago Press.

Klinenberg E. (2018). Palaces for the people : how social infrastructure can help fight inequality polarization and the decline of civic life (First). Crown.