What Can the AIDS Crisis Teach Us About Community Inclusion in Networks?

By Marissa Baron & Jenny Lawlor

Research shows that community coalition and collaborative network effectiveness is connected to member participation, diversity, and group cohesion (Zakocs & Edwards, 2006). To realize this in practice, networks must be set up with engagement in mind. Two theoretical perspectives offer guidance about how networks might do this: critical systems heuristics and the exchange boundary framework (Ulrich, 2005; Watson & Foster-Fishman, 2011).

What Are Critical System Heuristics?

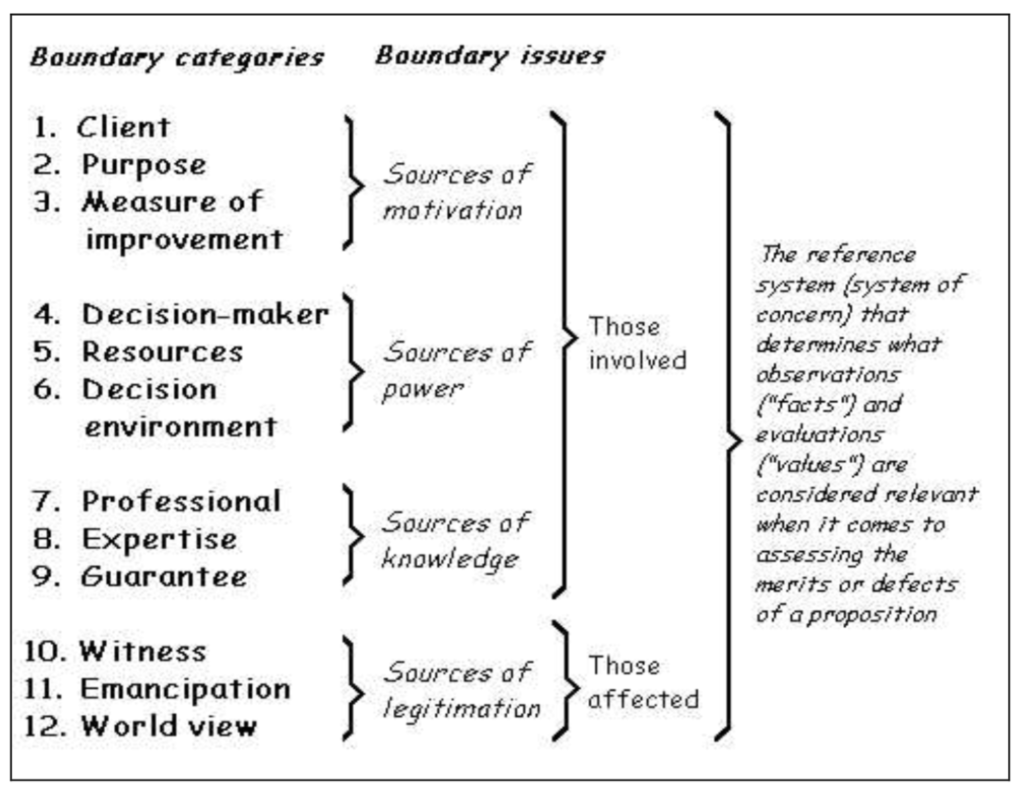

Critical system heuristics invites network participants to engage in boundary critique, critically considering who is included, who is excluded, and the stakes involved. This is especially important for network efforts where membership and participation boundaries are often established by a subset of participants. Ulrich (2005) suggests domains for this critique that include sources of:

- Motivation (e.g., whose interests should be served?),

- Power (e.g., who is in a position to make decisions?),

- Knowledge (e.g., who is considered an expert?),

- Legitimacy (e.g., what worldviews are considered and how are multiple worldviews reconciled?).

Network members can consider the current state of their network boundaries (‘what is’) relative to their desired state (‘what ought to be’) for each of these domains.

The Exchange Boundary Framework

Watson and Foster-Fishman (2011) also highlight the importance of considering how boundaries are drawn in networks, while adding a focus on the importance of expanding resource exchange among members. Critically drawing boundaries for engagement in a network can create a space for a diverse group of participants to work together. Resource exchange among participants makes it possible for the group to engage the full knowledge and resources each participant brings.

If participants are included in an effort, but others do not value their resources, the network risks tokenizing participants. If there are individuals whose resources are valued by network members, but they are not included in the network boundary, the network risks coopting them. Watson and Foster-Fishman argue the path to increasing power for network members is through the combination of inclusion in network boundaries and the valuing of participants’ resources within the network. .

The Community-Centered Approach to Engagement in Collaborative Networks

Critical systems heuristics (CSH) and the exchange boundary framework illustrate the need for a community centered approach when it comes to engagement across collaborative networks. According to Ulrich’s (2005) CSH, there are four sources of boundary issues, each of which leads to three types of boundary problems (Figure 1). These boundary problems do not just consider what issues arise within a situation across the network but also who is involved. Based on these boundary categories, those involved are centered around the categories across the sources of motivation, the sources of power, and the sources of knowledge. For those affected, they are centered in sources of legitimation. Nonetheless, what happens when there is a disconnect in those involved versus those affected to best address these boundary issues?

What is a Community-Centered Approach in Practice?

A community-centered approach “mobili[zes] assets within communities, promot[es] equity and increase[es] people’s control over their health and lives” (NHS England, 2015). A community centered approach ensures that the needs of those most impacted by the boundary issue(s) the network is working to address can utilize their capabilities and assets, through their own lived experiences, in leading the implementation of the work itself. Moreover, approaches that are community-centered move beyond receiving input from community members and instead empower individuals by providing multiple pathways for participation and decision-making.

Rather than distinguishing between those involved and those affected in boundary issues, a community-centered approach within a network utilizes Ulrich’s (2005) boundary categories but centers those affected as those also involved across each of the twelve categories. Social network analysis, with a community-centered approach to Ulrich’s CSH and exchange boundary framework, allows for strategic identification and assessment of such lever points across the network that will ultimately address the proper sources for collaboration with community leaders and those with lived experience as network members while reducing unintended negative repercussions by organizational network members that may lack this personal connection to the issue(s) the network aims to address.

An Example of a CSH Community-Centered Network in the AIDS Crisis

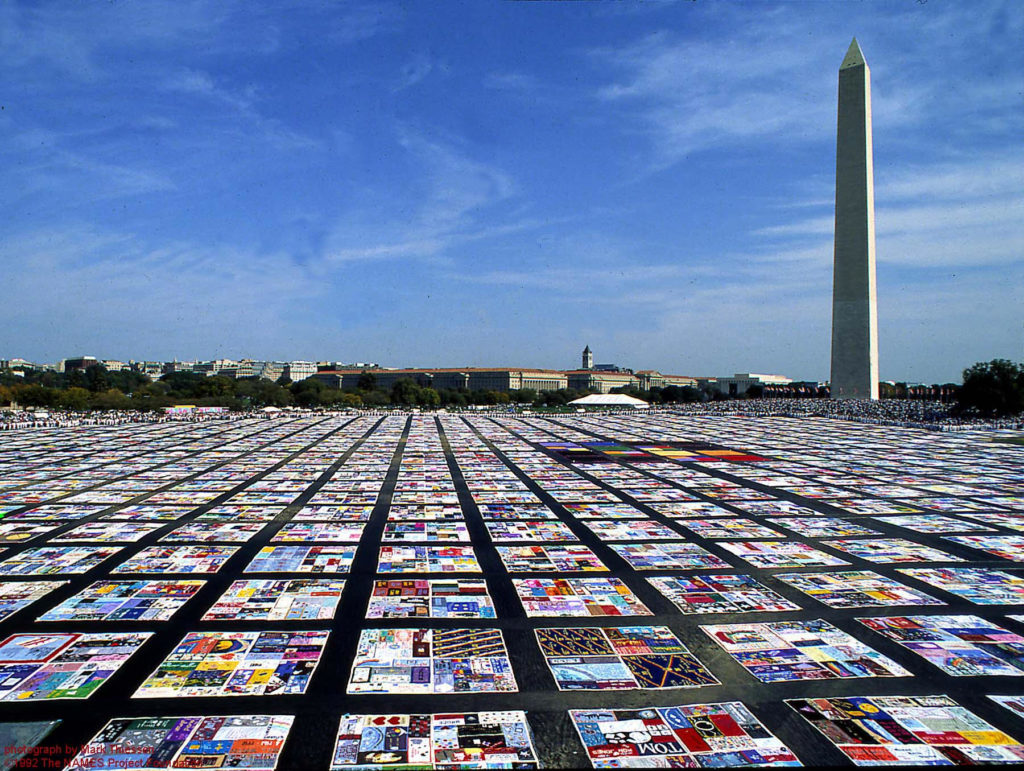

An applied example of a CSH community-centered network stems from the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. By 1987, with the death toll in the United States reaching 40,000, while millions globally continued to be diagnosed, the LGBTQ+ community’s mounting frustration for lack of treatment finally reaching a pivotal point of action. Seize Control of the FDA took place on October 11, 1988. This action, led by the community-led group ACT UP, was the organization’s first national action. Approximately 1,500 activists–those involved and affected–from across the country descended on the headquarters of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in Rockville, MD to demand that the Administration speed up the research, development, and approval of drugs for AIDS.

ACT UP demanded the following: (a) that the FDA speed up the approval process and release the information of all drugs being tested; (b) that people with AIDS have control of their decisions when choosing to take a drug; (c) that health equity across age, gender, race, and those with disabilities in who was included in trials is a requirement; (d) that placebos are eliminated from being used in these trials; and (e) that private insurance and Medicaid cover these treatments (Colman, 2014; Aizenman, 2019).

The members of ACT UP knew that the FDA had the power within the network addressing the AIDS crisis to legally change the approval process, and that is why they chose the FDA. The group recognized that if they put enough pressure on the FDA, the results would be tangible—and perhaps even revolutionary to a shift in progress and a shift in power across the network (Office of Public Health Practice and Training, JHSPH, 2018).

ACT UP's Approach to Community-Centered Advocacy

Utilizing both sources of knowledge and legitimation, ACT UP leveraged a network structure with loosely connected affinity groups to divide up important aspects of their work (e.g., Media Committee, Treatment and Data Committee) while sharing information across them, both locally and nationally. In addition to this effective structure, ACT UP’s success was largely in part due to the diversity of community members across the various chapters, though all with the common goal of addressing their and their communities’ experiences living with AIDS.

Furthermore, the organization provided a space for those with lived experience to share in their grief and their anger. Through trust built across the membership and empathy shared in a common source of motivation among those involved and affected, a sense of safety was provided for those directly impacted to be activated in an impactful and effective manner. By having this space and dividing membership across these affinity groups to engage in various aspects of the action(s), ACT UP really solidified itself during the planning for the action (Aizenman, 2019; Office of Public Health Practice and Training, JHSPH, 2018).

While many of the affinity groups within ACT UP were first created for this action, others like the Media committee and the Treatment and Data committee consolidated their relevance by showing how effective they were at both gathering research and planning, while developing and publishing digestible materials (Colman, 2014).

Spanning Boundaries with ACT UP

This national action was intended to garner the necessary support to truly make a difference and bring about systemic change. The ACT UP membership thought it was time to plan an action that could involve the many ACT UP organizations that had been activated throughout the nation. Due to the nature of the Treatment and Data Committee inside ACT UP NY, the group was already connected within the network to the FDA, interacting with the FDA on matters of increased access to medications, which at this time, they felt was the main issue to address (Colman, 2014; Office of Public Health Practice and Training, JHSPH, 2018).

As members of the Treatment and Data Committee served as boundary spanners, connecting the larger mobilization effort on the ground with those working within the FDA, the group was able to leverage their source of power. The most crucial component of the endeavor, according to the group, was to break through the bureaucratic red tape of the FDA and re-envision healthcare in the United States, centering membership of those both affected and involved, across all four boundary issues (Ulrich, 2005).

Restructuring the System to Focus on Patient Needs First

One of the key objectives of ACT UP was to convince the public of the need to restructure the healthcare system such that patients’ needs came first. The FDA acted at the nexus of the government, the private sector, and the public. As such, ACT UP identified their source of power and legitimation in directing their action at the Administration, to alter how the FDA interacted with both the government and the public throughout the network (Office of Public Health Practice and Training, JHSPH, 2018). Furthermore, ACT UP was able to develop a novel model for patient advocacy within the research system thanks to its efforts, including Seize the FDA (Colman, 2014; Aizenman, 2019). Today, it appears commonplace for those suffering from disease (i.e., a membership that includes those involved and affected) to have a place at the table for research and treatment—this was certainly not the norm before ACT UP and the AIDS crisis.

Community-Centered Focus at the Local Community Level

On a local level, the San Francisco Health Department (SFDPH) engaged in a similar approach across their network, though from the organizational level as those outside of the affected member group. The Department took a particularly vigorous stance against AIDS because of the LGBTQ+ community’s political influence in the network–identifying the groups’ source of power and source of legitimation. The community clamored for the quick creation of services after realizing the terrible threat that AIDS posed. In 1983, the SFDPH established the AIDS Office as the demand for assistance and intervention strategies against prevention grew. The Department made the decision to establish a separate AIDS Office primarily because the rest of the Department was unable to respond quickly enough to the enormous demands of this newly emerging epidemic (Katz, 2007).

The Office established several guiding principles on how to carry out its duties, including the significance of avoiding typical governmental decision-making processes in favor of creating procedures for participatory decision-making with the community–highlighting the need to center those affected and ensure their active involvement across boundaries. This is currently the paradigm that rules the Department as a whole.

For instance, in 1995 the Department met with paramedics, firefighters, private ambulance companies, union leaders, emergency room doctors and nurses, and citizen representatives to discuss how to better coordinate pre-hospital care for San Franciscans who dial 911. The inclusivity ethos and consensus-building techniques that the SFDPH had been applying frequently at the AIDS Office for several years were unfamiliar to many of the participants. Members of the committee were pleasantly surprised by the Department’s readiness to let the process decide on the new pre-hospital care design, and that, despite years of back-and-forth, they could come to an agreement on how to configure services (Katz, 2007).

Learning from the Design and Implementation of HIV/AIDS Programs

We can also learn about community engagement from the design and implementation of HIV/AIDS preventative interventions and programs. Miller et al. (1998) highlight the need for understanding interventions designed by researchers and tested experimentally in community-based settings with a perspective toward ongoing implementation. The authors also note the importance of research to support community-designed interventions. This means that effective intervention development and implementation involves both inclusion of multiple groups (setting appropriate boundaries around who is involved in the effort) and valuing the knowledge and resources those individuals bring to the process.

The authors replicated an experimentally tested intervention that uses network structure to change social norms among men at hustler bars in New York City. The intervention drew on diffusion of innovation theory (Rogers, 1995), which suggests that social norms diffuse through communities and that a small set of key opinion leaders within a community can often drive diffusion. In this intervention, bartenders were trained to identify key opinion leaders who were trained to hold conversations about safe sex practices.

These conversations diffused through the network as non-key opinion leaders also shared the practices with their connections. This work focuses on creating change by taking advantage of network structure (known as ‘network interventions’), AND it highlights the need to consider multiple vital groups and their relationships (in this case, academic and community groups) to support the ongoing implementation of effective interventions.

Learning from the AIDS Crisis Can Help Us Better Engage and Include Communities in our Networks

The AIDS crisis rekindled community empowerment and activism as mechanisms for engagement across boundaries within a network. This is particularly important for effective actions as prevention measures before reaching a crisis point within networks (such as occurred in the AIDS crisis). As such, these tactics have proven useful across health networks addressing a variety of areas. For instance, many networks now collaborate with seniors and persons with disabilities to develop strategies for improving pedestrian safety. Other networks aimed at addressing the needs of those experiencing substance dependence engage those individuals by organizing injectable drug users to learn CPR and how to give Narcan to their community members who may be susceptible to overdose.

Furthermore, It is critical to be intentional about the roles researchers and community members play when designing programs and interventions, but also when such programs are implemented. Ensuring communication and collaboration among groups with different perspectives, skills, resources, and lived experience makes it possible to develop community centered programs and interventions that can create effective and sustainable change.

References and Additional Resources

Aizenman, N. (2019). “How To Demand A Medical Breakthrough: Lessons From The AIDS Fight.” NPR, February 9, 2019. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/02/09/689924838/how-to-demand-a-medical-breakthrough-lessons-from-the-aids-fight.

Colvin C. J. (2014). Evidence and AIDS activism: HIV scale-up and the contemporary politics of knowledge in global public health. Global public health, 9(1-2), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2014.881519

Katz M. H. (2005). The Public Health Response to HIV/AIDS: What Have We Learned?. The AIDS Pandemic, 90–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012465271-2/50007-8

Miller, R. L., Klotz, D., & Eckholdt, H. M. (1998). HIV Prevention with Male Prostitutes and Patrons of Hustler Bars: Replication of an HIV Preventive Intervention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 26(1), 97–131. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021886208524

NHS England. (2015). A guide to community-centred approaches for health and wellbeing. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/768979/A_guide_to_communitycentred_approaches_for_health_and_wellbeing__full_report_.pdf

Office of Public Health Practice and Training, JHSPH. (2018, October 17). 30th Anniversary of “Seize Control of the FDA” — Protest, Crisis and Public Health. www.youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=slMBTH2GX74

Ulrich, W (2005). A brief introduction to critical systems heuristics (CSH). ECOSENSUS project website, The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK, 14 October 2005 http://projects.kmi.open.ac.uk/ecosensus/publications/ulrich_csh_intro.pdf

Watson, E., & Foster-Fishman, P. (2012). The Exchange Boundary Framework: Understanding the Evolution of Power within Collaborative Decision-Making Settings. American Journal of Community Psychology, 51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9540-8