Network Science: A Reference Guide

William Jacobson

Network science. We engage in it everyday, knowingly or not. But how? And what is it?

Networks are all around us. Human beings have formed and utilized networks from the beginning of humankind; to hunt, gather and prevent inbreeding, to begin revolutions and wage war, and to socialize and govern.

But, really — what is network science? What is centrality? Density? And just how strong is the “Strength of Weak Ties“?

Below, you’ll find definitions and resources to Introduction Topics – basic terms that are essential for understanding network analysis and science, listed from general to more specific. Following the Introduction Topics are more specialized terms, listed alphabetically.

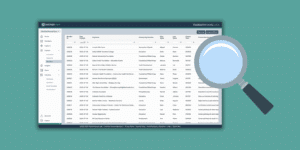

The reference guide is then rounded out with definitions and explanations of terms used by our Data Science team while utilizing our PARTNER CPRM (Community Partner Relationship Management) platform to help organizations map, track, and visualize their network. Read on to grow your knowledge in network science.

Introduction Topics

Network Science:

Network science is the study of networks. Network scientists work to understand how different network factors, like their structure, quality, and context affect network outcomes. Network Science is studied in academia, and involves the examination of complex networks.

A simple definition of a network is “a group or system of interconnected people or things.” This can refer to social networks (which we map with PARTNERme), organizational networks (which we map with PARTNER CPRM), computer networks, telecommunications networks, biological networks, and so on.

Learn More:

A Gentle Introduction to Network Science: Dr Renaud Lambiotte, University of Oxford – Video

Network Science Concepts Drawn From Real Life, History, Basic Ideas

Social Network Analysis (SNA):

Social network analysis is a way to understand how networks behave, and uncover the most important nodes within them.

“Social Network Analyis (SNA) is a collection of methods and tools that could be used to study relationships, interactions and communications. As such, SNA is suitable for the study and possibly monitoring of online interactions as it can automatically analyze interaction data, bringing a bird-eye view of the group social structure, the interaction patterns, as well as the mapping of all communications in the relational space. SNA can be implemented in two main ways, visualization, and mathematical analysis.” – BMC

“Social network analysis (SNA), also known as network science, is a field of data analytics that uses networks and graph theory to understand social structures. SNA techniques can also be applied to networks outside of the societal realm.

In order to build SNA graphs, two key components are required: actors and relationships. A common application of SNA techniques is with the internet. Web pages on the internet often link to other web pages — either on their own website or another website. These links can be considered relationships between actors (web pages). This is actually a key component of search engine architecture.” – Towards Data Science

Learn More:

It’s A Small World, Kristen Bell: The Invisible Networks Linking Us All

Aggregated Articles on Social Network Analysis

The Ethics of Social Network Analysis: What Could Go Wrong?

Using Social Network Analysis to fight Gang Crime in UK Urban Areas

Node:

“A network is simply a number of points (or ‘nodes’) that are connected by links. Generally in social network analysis, the nodes are people and the links are any social connection between them – for example, friendship, marital/family ties, or financial ties.” – Social Network Analysis – How To Guide

Key Player:

A key player is identified as one of, or the most central node in a network. Key players have more connections than others, and also likely help facilitate connections in the network. If a network were to lose its key player, it would have an outsized effect, greater than the loss of any other nodes in the network.

Learn More:

Covert Network Analysis for Key Player Detection and Event Prediction Using a Hybrid Classifier – Key Player analysis, adapted for national security and law enforcement use

Degree:

One of the most simple network metrics, it measures how many nodes each node is connected to. It can be averaged across the network to give the average degree of the network, an approximation of the network’s connectedness.

Centrality Measures

Centrality:

Centrality, and its measures refer to the extent to which a node is connected to its surrounding nodes and is “central” to the network. This helps us know who the “key players” in the network are, allowing us to build strategies on how to leverage or shift their positions to achieve key outcomes. There are a few measures of centrality, like betweenness, closeness, and degree centrality – all of which are covered here.

Centrality measures address the question: “Who is the most important or central person in this network?

Learn more:

Understanding Network Centrality

Network Structure: Who, What, Why?

Social Network Analysis 101: Centrality Measures Explained

Network Centrality Slide Deck – Definitions and Formulas

Aggregated Network Centrality Resources

Betweenness Centrality:

This is a measure of how often a node is in the shortest path between two other nodes in the network. People or organizations with high betweenness centrality scores are often considered gatekeepers of information and resources. In this example, the most central node falls in the shortest path between four other pairs of nodes in the network. The least central node doesn’t fall on the shortest path between any of the other nodes in the network.

“Betweenness centrality quantifies the number of times a node acts as a bridge along the shortest path between two other nodes. It was introduced as a measure for quantifying the control of a human on the communication between other humans in a social network by Linton Freeman.” – Donglei Du, University of New Brunswick

Learn More:

Understanding Network Centrality

Network Structure: Who, What, Why?

Social Network Analysis 101: Centrality Measures Explained

Network Centrality Slide Deck – Definitions and Formulas

Aggregated Network Centrality Resources

Closeness Centrality:

“This is a measure of closeness or distance to others in the network. More central nodes can communicate more quickly and easily with others in the network compared to less central nodes. More central nodes have low closeness centrality scores and do not have to “travel” as far along paths to get to others in the network. Nodes with high closeness centrality scores are less central and have to travel farther along the paths to get to others in the network.” – VNL Infographic

“Closeness centrality indicates how close a node is to all other nodes in the network. It is calculated as the average of the shortest path length from the node to every other node in the network.

Closeness centrality measures each individual’s position in the network via a different perspective from the other network metrics, capturing the average distance between each vertex and every other vertex in the network. Assuming that vertices can only pass messages to or influence their existing connections, a low closeness centrality means that a person is directly connected or “just a hop away” from most others in the network.” – Science Direct

Learn More:

Understanding Network Centrality

Network Structure: Who, What, Why?

Social Network Analysis 101: Centrality Measures Explained

Network Centrality Slide Deck – Definitions and Formulas

Aggregated Network Centrality Resources

Degree Centrality:

“This is a measure of the number of connections each node has in a network. People or organizations directly connected to others are considered more central as they can access or deliver more resources and opportunities. In this example, the most central node is directly connected to five others in the network. The least central nodes are only connected to one other node in the network.” – LINK

“Though simple, degree is often a highly effective measure of the influence or importance of a node: In many social settings people with more connections tend to have more power and be more visible.” – Donglei Du , University of New Brunswick

“Degree centrality is the simplest centrality measure to compute. Recall that a node’s degree is simply a count of how many social connections (i.e., edges) it has. The degree centrality for a node is simply its degree. A node with 10 social connections would have a degree centrality of 10. A node with 1 edge would have a degree centrality of 1.

Sometimes, a SNA program will convert those numbers into a 0-1 scale. In such cases, the node with the highest degree in the network will have a degree centrality of 1, and every other node’s centrality will be the fraction of its degree compared with that most popular node. For example, if the highest-degree node in a network has 20 edges, a node with 10 edges would have a degree centrality of 0.5 (10 ÷ 20). A node with a degree of 2 would have a degree centrality of 0.1 (2 ÷ 20).

For degree centrality, higher values mean that the node is more central. As mentioned above, each centrality measure indicates a different type of importance. Degree centrality shows how many connections a person has. They may be connected to lots of people at the heart of the network, but they might also be far off on the edge of the network.” – Science Direct

Learn More:

Understanding Network Centrality

Network Structure: Who, What, Why?

Social Network Analysis 101: Centrality Measures Explained

Topics Listed Alphabetically

Cooperation:

Having awareness of a relational partner AND informally exchanging information, attending meetings together, and sharing in-kind resources. A goal for most networks is to have high percentages of cooperative and coordinated relationships.

Coordination:

Cooperating with a relational partner, AND synchronizing activities for the mutual benefit of services and/or programs (e.g., sharing proprietary data, timing events/activities together).

A goal for most networks is to have high percentages of cooperative and coordinated relationships. In networks in which mission alignment is particularly important, coordinated relationships may be desirable.

Cliques:

A sub-group of densely connected nodes that can be recognized as a distinct community within the larger network.

Density:

Percentage of ties present in the network in relation to the total number of possible ties in the entire network, if everyone was connected to everyone else.

Density Interpretation:

Density can be seen as an indicator of interconnectedness. Holding the number of nodes in a network constant, an increase in connections between the nodes means an increase in density. To achieve a 100% density score, every member of the network would have to be connected to every other member.

Based on our (VNL’s) database of over 4,000 inter-organizational networks that have been analyzed using the PARTNER Platform, we use the following scale to assess density scores:

- Low: <20%

- Moderate: 20-60%

- High: >60% – LINK

Learn More:

An Intro to PARTNER’s Validated Measures – Visible Network Labs

What is Network Density – and How Do You Calculate It?

Edge:

A fancy term that just means a line connecting two nodes and denoting a connection exists between them.

Integration (High):

Coordinating with a relational partner, AND entering into mutual, binding relationships that support work in related content areas (e.g., through contracts, grants, MOUs, pooled funding with collective implementation).

When thinking about relational integration, we tend to revert to the conventional wisdom that “more is better,” and of course a highly integrated relationship may yield many benefits. Keep in mind, however, that there are also drawbacks to high integration: the greater the degree of integration, the more time and effort the relationship likely requires. A network with relatively high percentages of integrated relationships may be at risk for member burnout and eventual disengagement.

Learn More:

An Intro to PARTNER’s Validated Measures

Path Length:

The number of nodes/connections that link two indirectly connected nodes (degrees of separation)

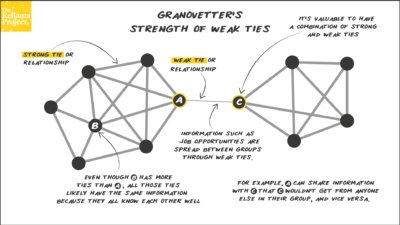

Strength of Weak Ties:

A 1973 empirical paper published by Stanford sociology professor Mark Granovetter, where he concluded that “In social networks, you have different links — or ties — to other people. Strong ties are characterized as deep affinity; for example family, friends or colleagues. Weak ties, in contrast, might be acquaintances, or a stranger with a common cultural background. The point is that the strength of these ties can substantially affect interactions, outcomes and well-being.

Granovetter wondered if strength of ties had an impact on finding a job. His insight was that within a network of strong ties, people with weak ties outside the core network are bridges to other networks. Those bridges have access to new and unique information — like job openings — relative to other members of the network with only strong ties.

In particular, Granovetter showed that people with weak ties not only find jobs that the rest of the tight network cannot see, but those jobs come with higher compensation and satisfaction. This is especially true for higher-educated workers, like your typical engineer. Because more than 40 percent of jobs are found through referrals, understanding weak ties is an important factor for both job seekers and recruiters.” – Tech Crunch

Strong Tie:

A firm relationship with significant trust. Often found between families, friends, and those who share the same social circles.

Weak Tie:

An acquaintanceship with less trust than a strong tie, often found between colleagues and coworkers, distant friends and relatives. Because weak ties tend to share different social circles, they expose you to more novel ideas and opportunities than your strong ties.

The following terms, listed alphabetically, are primarily applied by the Visible Network Labs’ Data Science team while using our PARTNER CPRM platform.

Awareness:

Having basic awareness of what a relational partner does (e.g. understanding of services offered, resources available, mission/goals).

A network with relatively high percentages of awareness relationships may be newly formed, or may be attempting to encourage relationships among organizations that typically don’t interact. To capitalize on collaborative advantage, networks should attempt to convert many of its awareness relationships to those of higher intensity. However, don’t underestimate the strength of weak ties. Basic awareness can lead to the discovery of new resources, contacts, etc., for an organization.

Intensity:

A PARTNER CPRM scale that measures relationship intensity. The question prompt asks, “What is your organization’s dominant way of interacting with this organization?” For more information, check out An Intro to PARTNER’s Validated Measures.

Relationship Intensity Interpretation:

Can be used as a measure of tie “strength.” Scale, from low intensity to high.

In Support of Mission:

The organization is perceived as being committed to the shared mission or goal of the network.

Level of Involvement:

The organization is committed to and actively involved in achieving network goals. The organization gets things done.

Overall Trust Score:

A PARTNER CPRM measure of how much members trust one another by capturing members’ perceptions of others along three dimensions: reliability, mission alignment, and openness to discussion. The overall trust score reflects the average of the scores along the three dimensions. Assessed at both the whole network and individual node levels.

Overall Trust Interpretation:

Survey respondents rate each dimension of trust on a scale of 1 to 4 (1 = not at all, 2 = a small amount, 3 = a fair amount, 4 = a great deal). Scores of at least 3 out of 4, or 75%, are considered good scores. At the network level, if a network receives a 100% trust score (4/4), it would mean that all members reported the highest levels of trust of one another. If any dimension of trust receives a score under 3.0, this may indicate an area of growth for the organization. Each of the three dimensions of this combined score are considered equally important.

Overall Value Definition:

A PARTNER measure of how much members value one another by capturing members’ perceptions along three dimensions: power/influence, level of involvement, and resource contribution. The overall value score reflects the average of the scores along the three dimensions. Assessed at both the whole network and individual node levels.

Overall Value Interpretation:

Survey respondents rate each dimension of value on a scale of 1 to 4 (1=not at all, 2=a small amount, 3=a fair amount, 4=a great deal). Scores of at least 3 out of 4, or 75%, are considered good scores. At the network level, if a network receives a 100% value score (4/4), it would mean that all members reported the highest levels of value of one another. If any dimension of value receives a score under 3.0, this may indicate an area of growth for the organization. Each of the three dimensions of this combined score are considered equally important.

Open to Discussion:

The organization is willing to engage in frank, open and civil discussion (especially when disagreement exists). The organization is willing to consider a variety of viewpoints and talk together, rather than at each other.

Power/Influence Score:

The organization holds a prominent position in the community by being powerful, having influence, having success as a change agent, and showing leadership.

Reliable:

The organization follows through on commitments.

Resource Contribution:

The organization contributes resources like funding, information, staff time, meeting space, etc.

Interested in visualizing your network?

Here at Visible Network Labs, we make invisible networks visible, as our name suggests — at both the organizational and personal level.

We work closely with innovative organizations around the globe using our PARTNER CPRM platform, helping them map, track, and visualize their network, reach, and impact. PARTNER CPRM analyzes your data, identifying gaps and opportunities for more effective collaboration. With numerous report options and the ability to export network maps and visible network profiles, you can easily share your results with partners and the community to make the most of your data.

At the personal level, our PARTNERme platform utilizes social network analysis to take a person-centered approach to mapping an individual’s social support network. It then identifies their most pressing need with the least amount of support, and links them to helpful resources in the community to improve their health and quality of life.

Reach out to us here to schedule a demonstration on how our team can help you uncover insights in your work.

Be sure to stay tuned to our Visible Us Blog for more product updates and VNL Team content!

About the Author: Laura Johnson

Laura Johnson is a public health researcher with expertise in network science and the social and behavioral aspects of health. She is finishing her PhD in Public Health from the University of Nevada, Reno. While there, Laura has used complex quantitative analysis to explore the ways in which interpersonal social networks can have implications for women at-risk of HIV, such as their attitudes about medical mistrust, their thoughts on HIV prevention, or who they can turn to for health advice.

Prior to pursuing a PhD, Laura worked for 8 years in various academic, public-sector, and private-sector settings conducting quantitative and qualitative research to address a range of important social issues. Laura’s own personal networks have resulted in learning about job opportunities, adopting a dog, and meeting her spouse, among other transformational life experiences.