How Networks Helped Foster the American Revolution

Human beings have been creating, joining, and relying on networks since the beginning of our species. Research from an international group of academics found that early humans living in the area of what is now known as Sunghir – a famed archeological site in Russia during the Upper Paleolithic period (some 34,000 years ago), seem to have somehow understood the dangers of inbreeding. Living in small groups that survived by hunting, they developed social networks to facilitate matchmaking in ways that allowed for genetic diversity – protecting against inbreeding, and helping to ensure their survival.

Traveling in time to the later 18th Century, in what was then known as the “United Colonies” – Patriots demonstrated the power of networks and network leadership as the rebellion grew, by creating committees of correspondence in response to the heavy-handed policies and actions of King George III and Britain towards the 13 American colonies. These networks, like those in early human history, also helped ensure birth and survival – except this time, it was that of a nation.

Taxation Without Representation

Long before a version of the phrase “No Taxation Without Representation” would be seen emblazoned on the bottom of license plates on vehicles in Washington, D.C., it had a greater meaning to the Patriots living in the colonies in the later 1700s. The British victory in the Seven Years’ War (known to the colonies as the French and Indian War) had been costly, leaving that nation with significant debt. A strategy was devised to help pay the deficit, and continue to support the approximately 10,000 soldiers (referred to in the colonies as Redcoats) living in the colonies. The solution? Impose taxes on critical items imported to the colonies.

First, the British Parliament passed the Sugar Act in April 1764, taxing imports of sugar and molasses to the colonies. Shortly thereafter in March 1765, the Stamp Act required Patriots to pay taxes on every piece of paper used, and the Currency Act prohibited them from printing their own money, and prevented businesses in the colonies from paying their debts owed to British creditors with money issued from colonial governments.

The Loyal Nine

The Patriots were outraged. A network of local businessmen, who became known as The Loyal Nine, gathered at the building that housed the Boston Gazette in hopes of finding a way to head off the implementation of the Stamp Act in November of that year. Realizing they needed numbers, they connected with a shoemaker named Ebenezer Mackintosh.

Mackintosh had his own formidable network of ruffians; he was the leader of the South End gang of Boston, a rowdy group who got together each year on November 5th for “Pope Night”, a show of defiance against the Catholic Church. The Loyal Nine knew he was able to rally thousands of men on short notice. This he did on multiple occasions, igniting large protests against the Stamp Act.

These protests got increasingly chaotic, with some becoming riots complete with angry, violent mobs. On August 26th, 1765, a protest got out of hand, tearing through Massachusetts Lt. Governor Thomas Hutchinson’s opulent Boston mansion. Hutchinson got word of the approaching danger, and sent his family away. As the mob approached, Hutchinson finally fled. They broke down the doors with axes – subsequently taking or destroying almost everything in the house, including his family’s possessions, furniture, and his official public papers. By the end, there were even members of the mob pulling boards and slate from the roof of the home.

The Birth of The Sons of Liberty

The Loyal Nine were semi-prominent members of the community due to their business dealings, and although they participated in many of the protests, they hid their identities – leaving much of the legwork and notoriety to the “lower classes”. One observer of a protest led by Mackintosh saw a person dressed like a “workman,” but saw their trouser leg ride up, uncovering the silk stockings the man was wearing. After the destruction of Lt. Governor Hutchinson’s home, they merged into a larger network of Patriots who were also figures in the community, known as the Sons of Liberty.

In March 1766, after much protest and a persuasive appeal in front of the British House of Commons by Benjamin Franklin, who was at the time an Agent of Pennsylvania and the Deputy Postmaster General of America under the Crown, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act. But all was not well; the same day, Parliament passed the Declaratory Act of 1766, which gave Britain wider authority to tax the colonies.

Townshend Acts and The Boston Massacre

The next year, a British Chancellor named Charles Townshend imposed a duties act bearing his last name, which added duties on all British glass, lead, paint, paper, china, and tea imported to the colonies. These items were selected to be taxed because Townshend believed they would be cumbersome for the Patriots to manufacture themselves. An estimated £40,000 were to be raised over an unspecified period, which would pay the salaries of government officials in the colonies, cementing the loyalty of colony leaders to Britain.

In response, Benjamin Franklin sent word to Parliament that the colonies planned to begin manufacturing their own items instead of paying the duties. A boycott on British goods by the colonies began. News of the boycott was quickly and widely disseminated through the Sons of Liberty’s extensive network; 24 towns in Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island agreed to the boycott in January 1768, with towns in New York joining in April of that year.

Alarmed, but determined, King George III stationed 2,000 Redcoats in Boston, a city of only 16,000 residents at the time, to enforce the measures. Groups of Patriots, aided by the Sons of Liberty, were speaking to one another in underground networks, and turned their ire to these soldiers. Violent conflicts ensued, sparking a tragic incident, the infamous Boston Massacre on March 5th, 1770. After the smoke from the Redcoats’ weapons cleared, five Patriots were dead, and six were seriously wounded.

Committees of Correspondence

Unbeknownst to the Patriots, over 3,000 miles across the ocean and on the same day as the massacre, Lord North, the Prime Minister of Great Britain requested Parliament to repeal the Townshend acts. And repealed they were, with a caveat; all taxes, except those on tea, would be lifted. While this may have seemed reasonable, time would reveal that the Patriots did not agree.

A formal definition of Committees of Correspondence: “Committees of correspondence were longstanding institutions that became a key communications system during the early years of the American Revolution (1772-1776). Towns, counties, and colonies from Nova Scotia to Georgia had their own committees of correspondence. Men on these committees wrote to each other to express ideas, to confirm mutual assistance, and to debate and coordinate resistance to British imperial policy. The network created by committees of correspondence organized and mobilized hundreds of communities across the British North American colonies.”

In late 1772, news spread that the highest officials in the Massachusetts Bay Province would have their salaries paid by King George III – directly from Britain, instead of colonial legislatures. Network leader Samuel Adams raised alarm among his fellow Patriots that this jeopardized their right to equitable legal proceedings, pointing to the fact that judges would be beholden to King George III. Adams and the Boston Committee penned a letter to all towns in the province, communicating the news, and imploring towns to create their own committees and networks.

December 16th, 1773

Within six months, 118 towns in the Province created their own committees and networks, responding to Adams and the Boston Committee – thus creating the Boston-Massachusetts system, the first notable committee of correspondence in the 1770s. The newly established lines of communication served as a connection to Adams and the Patriots in Boston to the smaller towns, and were used often.

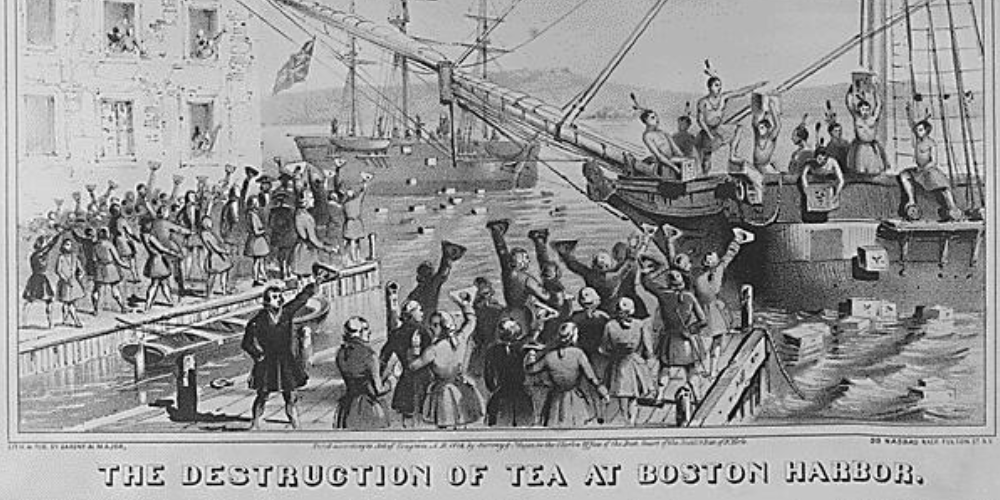

In December 1773, the Sons of Liberty knew ships carrying British-owned tea from China were arriving soon, and held meetings to organize and stoke opposition to the boats’ arrival, and the taxes on the tea they were carrying. On the morning of December 16th, 1773, as the British East India Company ships known as Dartmouth, Beaver, and Eleanor were docked at Boston’s Griffin’s Wharf, Patriots voted in favor of refusing to pay taxes on the tea; voting to not permit it to be “unloaded, stored, sold or used”.

That night, a party in Boston involving tea was held. Patriots, who were dressed as Native Americans, dumped 342 chests of tea into the harbor, breaking the chests open with tools before dumping them into Boston Harbor to thoroughly expose and destroy their contents. Collectively the chests held over 90,000 pounds of tea.

“The Shot Heard ‘Round The World”

Britain’s rage at this attack led to the Coercive Acts, known in the Colonies as the “Intolerable Acts”; a set of increasingly harsh laws and punishments from King George III. This led to the creation of a third significant committee of correspondence, the Post-Coercive Acts system.

Many smaller inter-colonial committees of correspondence requested a general congress be formed to thwart the Coercive acts. Thus, a meeting was convened in the Spring of 1774 of the First Continental Congress, a network of delegates from every colony except Georgia. The Congress came together in Philadelphia to discuss how to respond to the acts, producing the Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress.

Britain did nothing to quell the unrest. On the night of April 18th, 1775, Redcoats marched toward Concord, Massachusetts in a bid to seize a cache of weapons and ammunition that were kept there by Patriots. Along the way, they were surprised by 70 Minutemen – Patriots who worked in local networks, alert and ready to fight at a moment’s notice. A shot was fired; it remains unclear which side fired first. But what is known, though, is that it was “The Shot Heard ‘Round the World” – one that would shape world history for centuries to come.

About the Author: Will Jacobson

Will is the Marketing Intern at VNL, and he joined the company in October 2021. Originally from New York City, Will loves Colorado and all the outdoor life it has to offer. He is also a pretty big foodie! Will assists in content creation, marketing, and communications for VNL. He is finishing up his degree in marketing from the University of Colorado Denver.