Understanding Perceptions of Relationships Makes Your Network Stronger

To Work Together Authentically, We Have To Be Comfortable With Knowing Perceptions Of Each Other

A community partner on a project recently declared in a data meeting that “You cannot authentically engage people in a network unless you understand the perceptions we all have of each other!” We could not agree more. Even more importantly, we need some way to understand these perceptions; something other than our gut instincts.

Why Are Perceptions So Important?

Well, these are the real relationships that exist among members of a network. That is, our most real relationships are the perceptions we have of others and the perceptions they have of us. When I perceive a person to be my friend, and they do not perceive me to be their friend, it completely affects our relationship and our ability to maintain it. Misunderstanding the perceptions we have of one another can create challenges when we try to develop strong connections. If you are anything like me, you probably struggle at times with relationships – how to manage them, how to maintain them, and how to nurture them. I think about social connectedness every day and have yet to figure out the formula for perfect connectivity. However, I do know that when we clearly understand the perceptions that others have about our relationships, we’re better able to make sense of these challenges. We can eventually turn that into plans and ideas for how to build, and sometimes let go of, relationships.

While this feels very intuitive to us as individuals, we tend to ignore – or deemphasize – the value of understanding perceptions at the organizational, or professional levels. I am often struck by how much we assume that networks of organizations with a goal of working together towards a common goal are going to just happen, simply because a group of people are motivated to work together on an issue. There is an unspoken assumption that because building relationships is such an innate human behavior, we should be able to translate those experiences into building, managing, and evaluating networks. In fact, we pride ourselves on keeping our relationships formal and leaving our subjective perceptions of others out of the relationships, because they are, after all, professional. Network science provides frameworks for making sense of the patterns and complexities of these relationships. Further, I know that data is a powerful tool we can use when trying to do the nitty gritty work of managing groups of diverse people, organizations, and systems. But that data should come in many different forms, covering a range of types of information that can inform the strategies to develop meaningful action steps in building your networks.

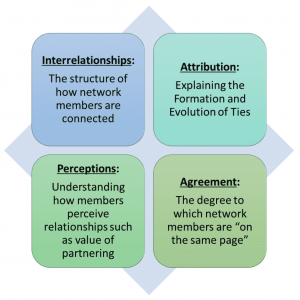

Over the last decade, after working with hundreds of cross-sector community networks, we have developed a framework to understand how to be effective network leaders and members. This framework includes four main areas to understand:

- The interrelationships of network members from a structural perspective. Who are the key players? Who are the bridging organizations? Who are central and who are on the periphery?

- How the network contributes to the development of relationships among members, the quality and content of those relationships, and whether the network intervention can be attributed to the outcomes.

- The extent that members of the network agree on how successful the network is at reaching its goals.

- The perceptions members have of each other regarding how valuable partnerships are, and perceptions of trust among members.

Understanding Perceptions Can Make Us Uncomfortable

It is the last point that is often the hardest for people to get comfortable with. While it is a hard to measure concept, we have also been conditioned to believe that perceptions are not the real relationships and therefore shouldn’t be guiding for us. However, when networks understand the perceptions members have of each other, they can leverage this information in ways that could be the difference between being effective or not. Why? Well, think back to the example of knowing if someone thinks of you as a friend. When we know the answer to that, we have a choice to make – we can reciprocate that friendship in a nurturing way, or we can choose not to invest more time in the relationship. We can also make other choices – like whether to introduce that friend to another friend, thereby strengthening the bonds between you all. You might even help connect them to other things you think they might want to know about, like jobs and other resources. There are a lot of decisions we make as we more deeply understand the relationships we are in – both to increase and decrease the amount of connectivity.

In order to truly leverage the power of a network, we are challenged to understand all kinds of complex relationships, but there are very few resources that help us create more visibility on these types of things. We understand that one reason people tend to deemphasize the need for this kind of information is because it is really hard to get the data and information we need. And yet, nothing about understanding social connectedness is that simple, is it?

We love measuring hard to understand concepts!

Fortunately, at Visible Network Labs we really love the challenge of understanding hard to measure concepts. When our community partners asked us to help them define and measure perceptions, we jumped at the chance, although this was not new work for us. In fact, when we did the initial research to develop the PARTNER Tool survey, we interviewed experts in the practice of making sense of complicated relationships and achieving collective impact. These early leaders had little guidance on how to do this work, but they certainly knew why they were doing it. When we posed the question “Why are you choosing a network approach to solve problems?” they have a number of answers that always funneled back into one broad purpose – they found value in building networks and partnerships. In fact, there were two things they told us with certainty – networks work when there is a perceived value in engaging with others, and when perceptions of trust is high. This felt intuitive to us, and it probably feels intuitive to you too! But that did not really give us all the information we needed.

So we went back to these experts to ask them to explain what value and trust in relationships “looked like”, how did they “know it was positive or negative”, and we asked them to describe what it “felt like” when they experienced high trust and value in relationships. This is where we made some real progress. After lots of coding and reflection among our team on the answers, we were able to identify the top three indicators of trust and value among members in networks.

Value was described as when partners were perceived to be:

- Powerful and Influential

- High in resource contributions

- High in commitment to the goals of the networks

Trust was described when partners are:

- Reliable

- Aligned with the mission of the network

- Open to discussion and transparent in communication

Something notable in these findings is that they are all embedded in perceptions of others – not physical characteristics that we can easily identify and see. For that reason, we integrated these six factors into measures of perception of trust and value within the PARTNER Tool survey. To this day, these scales of trust and value are the most valuable pieces of information that can come out of using the tool. And we published that study here.

How Are These Perceptions Used in Practice?

When networks make these perceptions visible to those leading the network (and especially when they make them available to the entire network), and they use that information to determine strategies for leveraging what they now know, they can be more efficient and effective. For example, when networks first form, they often identify the most powerful and influential organizations in the community to lead or be a part of the network. However, every other network in the community has also identified them as powerful and influential. It’s very likely that these organizations are playing leadership roles in many networks. The result are organizations that are stretched thin and lack shared leadership.

Yet, we found that value is also perceived when organizations contribute resources or demonstrate a strong commitment to the work of the network. When we understand who in the network is perceived to provide value through resources and/or commitment, we can leverage that value. That can act as a mechanism for developing shared facilitation, shared decision making, and shared accountability, making networks more effective. In our example above, we can tap into those organizations that have little perceived power and influence, yet who might have resources to contribute, or time to commit. When we leverage the varying types of value, and the ways that partners perceive each other, we can make meaningful strategic decisions to lead to greater effectiveness AND sustainability over time.

Not all Leaders are Powerful and Influential!

I will never forget the day I got a call from a PARTNER user, talking about all the things they learned from the social network data and mapping. She mentioned what turned out to be the most important finding in their assessment. According to her, they were convinced they were doing “everything right” – they had a diverse group of people representing a cross-sector of organizations working together, they were funded, and they had followed all the rules that other frameworks had guided them on. And still the needle on impact was not moving. Then she told me that she realized that everyone who was in a leadership role were the key organizations that were also in leadership roles in all the other community initiatives in their rural community. These were the ones perceived to be the most powerful and influential. It occurred to her that these organizations probably lacked the time commitment necessary to do the work they were being asked to do, and that the entire network was affected by this. She told me they were planning a “heart to heart” with their network to determine if they needed to redefine roles of leadership within the group. She admitted how hard this was when there are norms established in small communities about who is typically in charge.

Six months later we talked again. The network had decided to use their data to find those members perceived as having high commitment to the mission, but lacked perceptions of resources or power as contributions. These organizations were now in shared leadership roles and she reported they had accomplished some goals and reached some outcomes that they had previously been stuck on.

Let’s face it, we tend to lean on what we know. In networks, we elevate those that are perceived to be the most powerful and influential. But networks will not be effective if we tend to lean on only a few go-to organizations. It is when we tap into that leadership early on, but then work hard to develop shared governance and self-organizing processes that networks begin to gel and increase their propensity to both make the impact they hope for and sustain over time.

Understanding Diverse Perceptions is Powerful

If you are part of a network, in a network leadership position, or are a network evaluator, I would encourage you to embrace a norm that acknowledges the importance of perceptions in your work. Find ways to let people express these perceptions and then use the information to make decisions on how to leverage the information.

We are human and relationships are naturally what we work on every day. However that does not mean that we are naturally good at building and managing them, especially at the larger organizational level. We need data, we need science, and we need support to build our capacity to translate that data to our practice. At Visible Network Labs, we are obsessed with helping every network get the tools and information they need to make the greatest impact. We geek out about things like measuring perceptions in a network, but we also know how real and important these kinds of things are for people. When a community has committed to come together to talk about preventing suicide for Veterans, or a group of providers are committed to improving the system of care for babies and children with special healthcare needs – well, we will do everything we can to help them get the data, skills, knowledge, and abilities to make it happen!

About the Author: Dr. Danielle Varda

CEO, Founder, Professor, & Mother of Three Spirited Girls

Danielle is a scientist turned start-up founder, leading Visible Network Labs as CEO. Her combination of 20 years as a network scientist studying social connectedness and health, published author, 12 years as a tenured professor at the University of CO Denver, and her successful launch and scaling of the Center on Network Science came together in one big idea to start VNL. She is an entrepreneur, technologist, network scientist, fundraiser, and mother to three spirited girls. Her calling came when she realized her unique ability to develop technology solutions bridge complex systems science with everyday applications in communities, organizations, and business. She is a nationally known expert and keynote speaker on applied network science, with specific expertise in health system, public health system, entrepreneurial ecosystems, and educational system approaches. Danielle has published over 30 peer-reviewed articles on networks and their impact on health, well-being, and economic outcomes. Danielle leads VNL’s strategic partnership approach, is the company’s lead fundraiser, and has a vision for how to utilize network science to solve our most pressing and intractable problems.

In addition to her leading VNL, she is also an Associate Professor at the School of Public Affairs, University of Colorado Denver where she is Co-Director of the Center on Network Science, Director of the Nonprofit Concentration in the MPA program, and Advisor to the Dual MPA-MPH Degree. Additionally, she holds a secondary appointment in the Colorado School of Public Health, Department of Health Systems, Management, and Policy. She also has a courtesy Associate Professor appointment in the School of Information Sciences at the University of CO Boulder.